For years, more or less annually, the bit of the internet where gamers and game developers overlap has kicked off with aggro debate about “yellow paint”, a handholdy game trope where the player is constantly told explicitly what to do and where to go. I always feel a bit insane when this happens. A player thinks the paint is dumb, and then all the devs go “Yes, but you don’t understand, it’s unavoidable!“, but it’s not. You can be clear without being patronising. I’d argue that’s most of what game design is.

There are a million examples of developers guiding the player without their noticing, and the games that do it the best tend to be applauded the most. When a game does exhibit an inability to do that (or an abundance of yellow paint), I tend not to think it’s on account of anyone’s design incompetence as much as a management failure – a lot of folks work in places that don’t put a lot of trust in their designers, don’t allow any leaps of faith, and have a low tolerance for friction in a design; and that’s at the root of a lot of the worst issues in games right now – power in the wrong place.

I do, though, see a lot of folks railing against the expectation of competence in this area – players “demanding better” than constant ultra-overt guidance seems to be getting a lot of people’s backs up, and that strikes me as a pretty weird position for a designer to take. Often when I get into this with somebody I end up finding that something foundational I’ve always relied on in game design is not as ubiquitously accepted as I thought, and that thing is teach, reinforce, subvert, and I never see a game that does this also rely on yellow paint, or blocking tutorial screens, or NPC nags during puzzles, or anything in that loathesome genre.

Here are some favourite examples of times when a developer has taught something very deliberately and successfully without the player’s conscious knowledge. These shouldn’t blow many minds – players’ minds, maybe, but not developer minds – or at least I would have thought not, before this sort of discourse was a frequent event.

Here are the breakable boards from Half-Life 2.

Half-Life 2 has many boards, but they’re not all breakable. There’s never any ambiguity: these are the boards you have to break. They look like this. This is part of the visual language of Half-Life 2. If you see these, you gotta break ’em. Be a fool not to break ’em. Any others, maybe you can break ’em, but it’s not important. Break these. The boards tell you where to go. But that’s not enough, you have to teach it.

This part – where you have to break boards for the first time – happens the second you get the crowbar. You’re swinging it for the first time, hitting anything you can hit. And even though this game puts physics objects everywhere, there’s nothing else here to hit, and you can’t progress without hitting these. You weren’t told they were smashable, but you can’t leave this area without knowing that. Then the player knows about the boards! But that’s not enough. You have to reinforce it. There are more boards right after this. Then a crate. Then the boards again. teach and reinforce. The player has no choice but to internalise the crowbar and the boards and the smashing.

Now, because you didn’t tell the player about this with text, or yellow paint, or anything that would make the player consciously aware of it, you get to do something cool: subvert it. We taught that these are breakable, so now, later, when the player’s got to grips with the world more, we can have a zombie you thought you were safe from break these to get to you. This will scare you more because we didn’t tell you about it, but it won’t feel like bullshit. We can set up a situation where you have to be careful not to break them. We can use them as cover that the player will know isn’t great. We can have the player walk over a bridge made out of these and we’ll get, for free, the tension that comes with knowing they might break – and if they do, that won’t feel like bullshit either. You couldn’t have done this if you taught it overtly, because the expectation then is that if the player needs to know something you will teach it overtly. This is better. teach, reinforce, subvert.

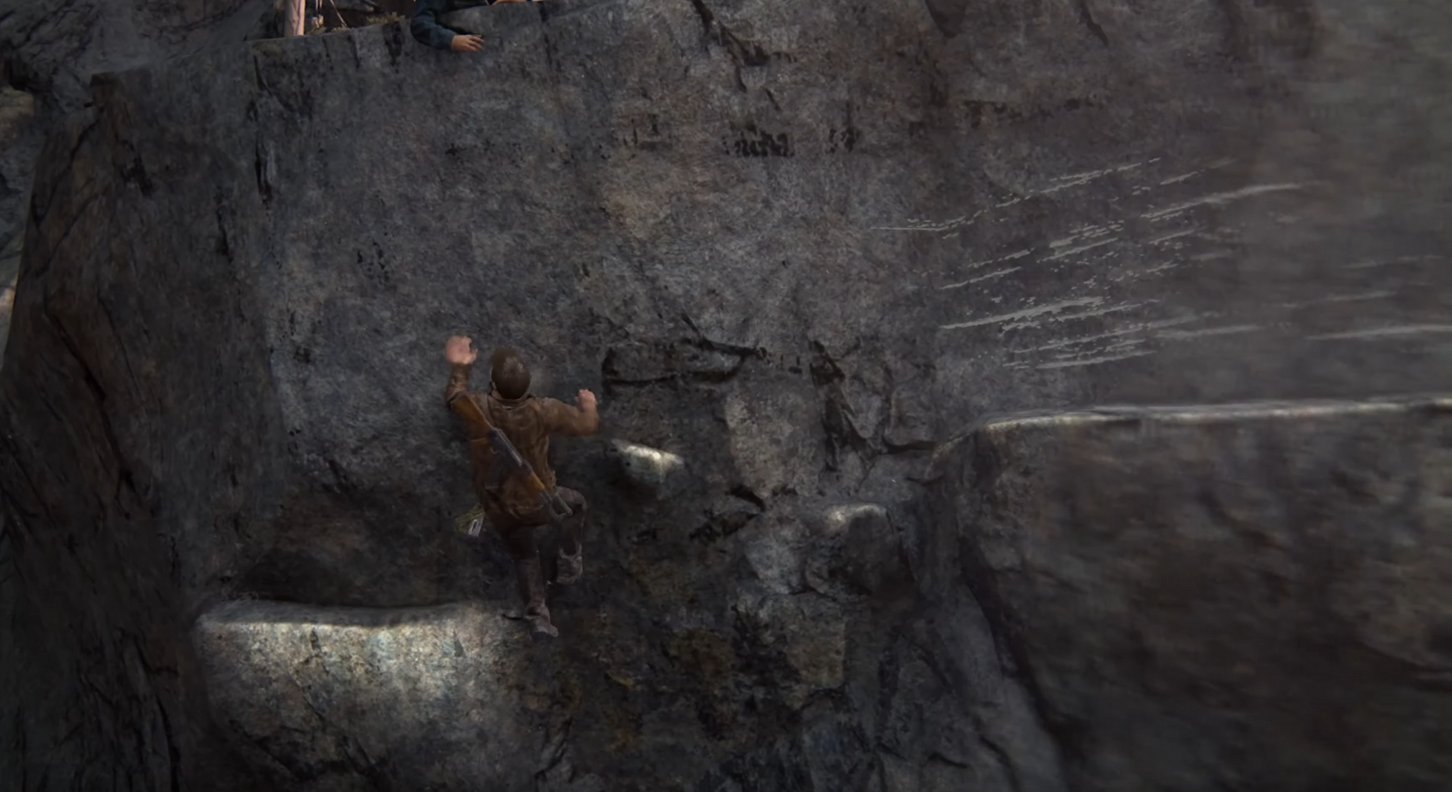

In Uncharted 4, every cliff ledge you have to grab has this overwrought edge-wear thing on it that you only get on climbable ledges. It’s not the yellow paint, but it gets you all of what’s good about the yellow paint, less overtly. Players aren’t complaining about this the way they do about the yellow paint, because it’s not insultingly obvious and arbitrary. It’s plausible in-world, and it tells you that you can climb here, not that you must climb here. And again, you can subvert it – Uncharted frequently does. Some of these break off unexpectedly and the player has to go another way. If, all game, you lead the player around with yellow paint, and then it leads the player into a trap, you’re just a dick. That’s bullshit. But if you lead the player around deftly, without them realising, that trap could be a great moment. Lighting is great for this – use orange light to mean safety all game, then have a monster bust through the wall of a warmly-lit room. The player’s shocked, but they don’t know we lied to them, so they’re not mad.

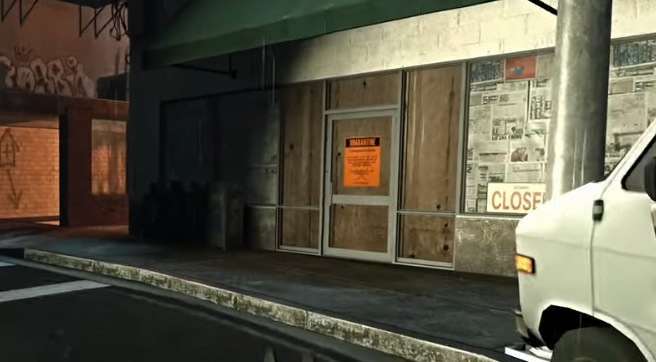

In Left 4 Dead 1, if you can’t open a door, you knew that already – it doesn’t look like you can. It’s visibly boarded up, or there’s no knob. There’s trash bags piled up in front of it. Someone’s pushed a vending machine over in front of it. Looking at it, the player decides, without thinking about it, not to try. The gamer brain knows it has no verb for this door. Most players will not rub up against set-dressing doors in this game expecting something to happen. But if we wanted, we could surprise the player by having a big monster break through one of these and we won’t have broken the contract.

In Portal 1, there are no climbable ladders, which can be a great design rule (famously one that Arkane are strict about). The player never climbs a ladder. But a ladder is used at one point in Portal – to make the player look up, which is famously really hard to do. When you see a ladder, you want to see where it goes, your gaze follows it up. Great trick. Here, the rungs fall off the wall when you touch them, but now you’ve looked up, and the goal caught your eye. The player knows where they’re going, and importantly, they think they figured it out on their own. A big part of why this works is that the ladder isn’t bright yellow.

Now sure, Portal’s environments are empty and flat, it’s close to a blank canvas visually. But I don’t buy that “games are more detailed now so this is harder”. Yeah, it’s a little harder, but that’s in your control. The job is the same. You still have access to all the old tricks of lighting and colour and composition. You don’t have to reach for a highlighter. The Last Of Us 2 is top of the list when people want to complain about modern photorealistic games being super visually dense, but you don’t get lost in that game’s wide-linear levels; it uses tricks like this all the time.

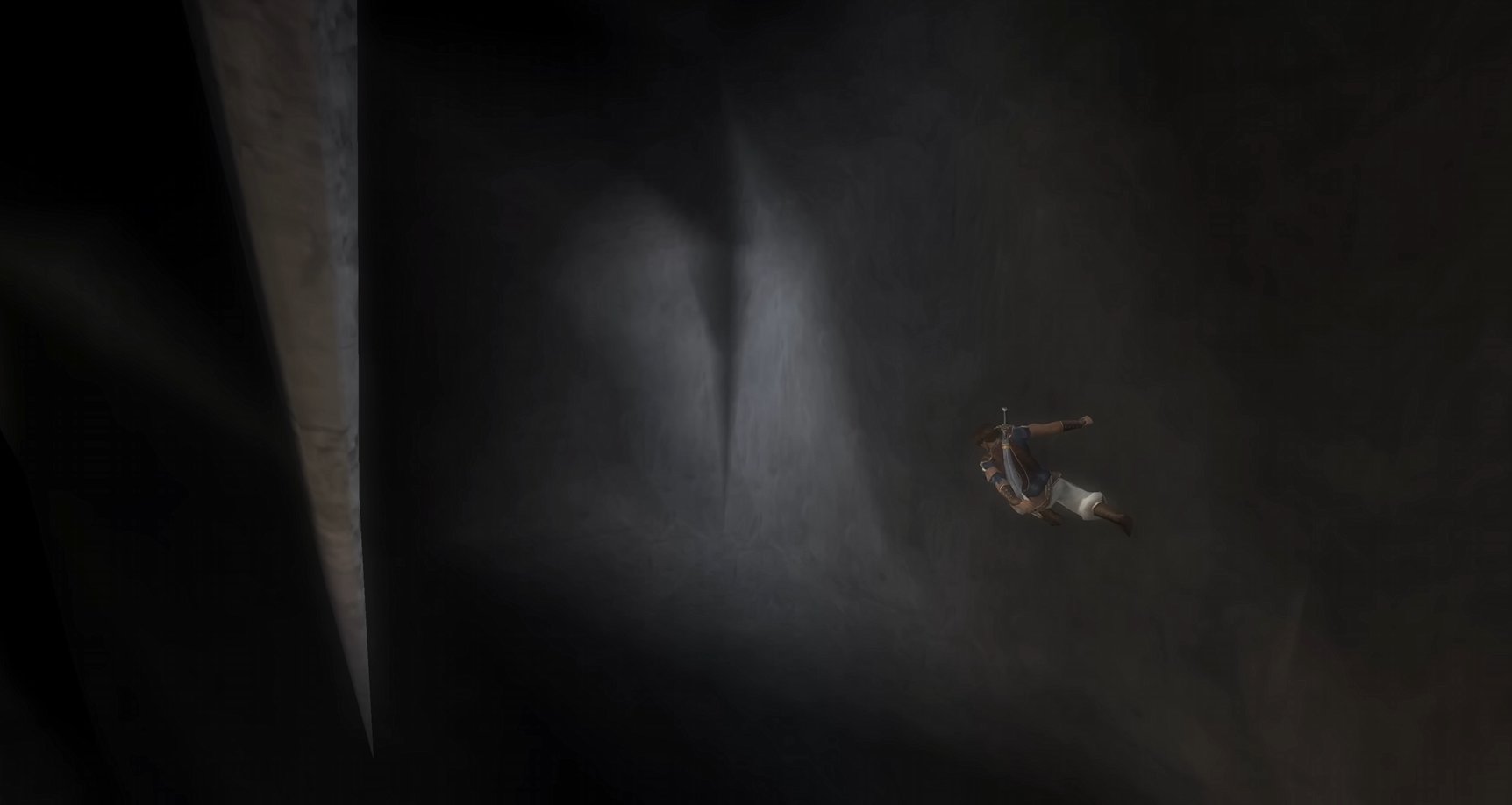

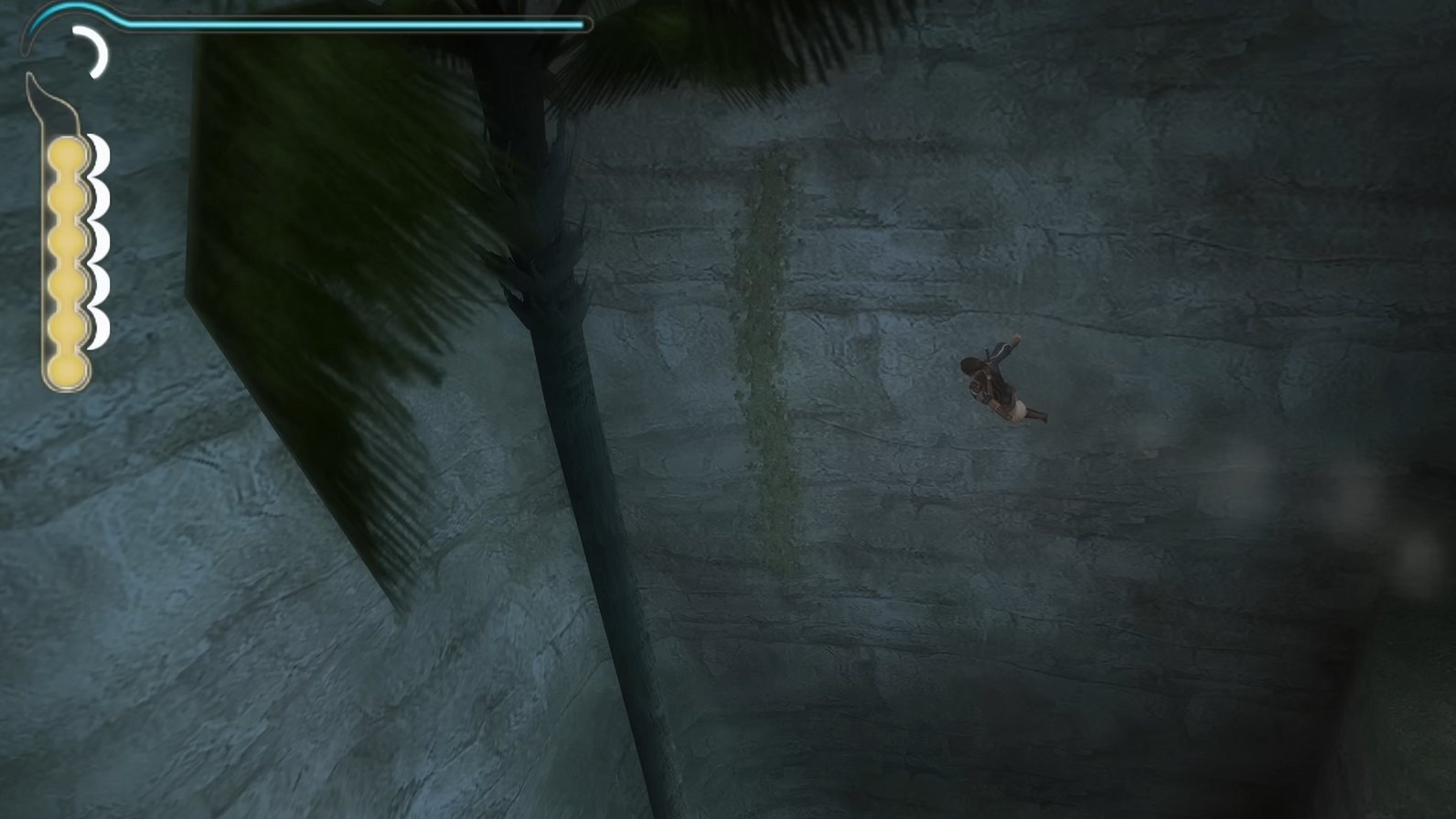

In Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, often you have to run along a wall and jump off it at the right time to grab something. The camera’s sometimes in your control, sometimes not. In the examples below, the player jumps when the Prince hits the perfectly-positioned shadow of the column he’s jumping to. The player does this automatically. Everyone gets it, nobody thinks about it, and it hasn’t been taught explicitly at all. These verbs – wallrun, jump, pole-climb – were introduced and reinforced earlier in safe situations. Later, they subvert this with fally-aparty poles.

So a lot of folks say that yellow paint is bad game design, but what I think it is is abdication of the task of game design; a non-engagement with the fundamentals. I don’t consider this to be a failure of (most of) the developers themselves; I think it’s about approaches taken by bosses and the pressures folks face at work that are so at odds with the doing of good work. People don’t take this approach because they want to. There are thoughtful and creative ways to solve all of these problems, and there’s no shortage of designers with the interest and motivation to do that who are just not given the time, trust or latitude by the people in charge (the wrong people). The implication of “Players won’t find their way if we don’t do this” as a design directive is “every player must find their way immediately”, which is the boss talking, and is no way to operate.

Someone, somewhere, has quit out of HL2 because they couldn’t figure out those boards, but you can’t compromise a creative work for that person. If you’ve made a film, and the audience loves it, but one guy walks out, you don’t figure that means you have to change the film. Games, like all art and all people, have to be allowed to be not for everyone if they’re to be anything to anyone.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.